Principal Nina Crone on one of her ground-breaking tours of China in 1984.

Principal Nina Crone on one of her ground-breaking tours of China in 1984.

Challenging the Norms

Tracing back through our history, the School’s archives reveal plenty of examples of strong and courageous educators challenging the norms of the present day. They demonstrate a focus and determination to provide our Grammarians with opportunities for a bright future whatever that may hold. The importance of learning, and a commitment to the pleasure of the rigour needed, is not new to Melbourne Girls Grammar.

Back in 1893, a teacher such as Ada Lambert epitomised a foundational pillar of our School – that it was one which educated women for the future – a future which in 1893 was not normally seen in terms of academic success for women. And yet, that was the focus of the foundational principals, Cambridge-educated Miss Emily Hensley and Miss Alice Taylor. They employed university-trained women, believing that it would open their students’ eyes to future possibilities. Ada Lambert was well on her way to a Master of Science at the University of Melbourne and was an excellent role model. She offered the girls exposure to a relatively rare school subject and an example of aspirations to further study. Much later, in the 1960s, Principal Edith Mountain reaffirmed this long-held commitment to the study of Science with the provision of laboratory facilities that were considered exceptional for the time.

Edith and Mary Morris, principals at the turn of last century, broke with tradition in introducing competitive sport as an intrinsic part of the curriculum offerings. They held fast against concerns about appropriate dress and behaviour for young ladies, focusing instead on the health benefits of exercise for the mind and body. This focus on health remains an integral part of our Artemis Centre today.

Back in 1893, a teacher such as Ada Lambert epitomised a foundational pillar of our School – that it was one which educated women for the future – a future which in 1893 was not normally seen in terms of academic success for women. And yet, that was the focus of the foundational principals, Cambridge-educated Miss Emily Hensley and Miss Alice Taylor. They employed university-trained women, believing that it would open their students’ eyes to future possibilities. Ada Lambert was well on her way to a Master of Science at the University of Melbourne and was an excellent role model. She offered the girls exposure to a relatively rare school subject and an example of aspirations to further study. Much later, in the 1960s, Principal Edith Mountain reaffirmed this long-held commitment to the study of Science with the provision of laboratory facilities that were considered exceptional for the time.

Edith and Mary Morris, principals at the turn of last century, broke with tradition in introducing competitive sport as an intrinsic part of the curriculum offerings. They held fast against concerns about appropriate dress and behaviour for young ladies, focusing instead on the health benefits of exercise for the mind and body. This focus on health remains an integral part of our Artemis Centre today.

Back in 1893, a teacher such as Ada Lambert epitomised a foundational pillar of our School – that it was one which educated women for the future – a future which in 1893 was not normally seen in terms of academic success for women. And yet, that was the focus of the foundational principals, Cambridge-educated Miss Emily Hensley and Miss Alice Taylor. They employed university-trained women, believing that it would open their students’ eyes to future possibilities. Ada Lambert was well on her way to a Master of Science at the University of Melbourne and was an excellent role model. She offered the girls exposure to a relatively rare school subject and an example of aspirations to further study. Much later, in the 1960s, Principal Edith Mountain reaffirmed this long-held commitment to the study of Science with the provision of laboratory facilities that were considered exceptional for the time.

Edith and Mary Morris, principals at the turn of last century, broke with tradition in introducing competitive sport as an intrinsic part of the curriculum offerings. They held fast against concerns about appropriate dress and behaviour for young ladies, focusing instead on the health benefits of exercise for the mind and body. This focus on health remains an integral part of our Artemis Centre today.

In 1925, Headmistress Miss Gilman Jones challenged the School to think about learning in a different way. She wanted the girls to take more responsibility and accountability for their own learning. Rather than traditional lock-step progression, she created a middle school, highly unusual for the 1920s and far ahead of its time. Grammarians became members of the three new houses, rather than of the traditional year levels and could chart their own progress across those years. They could choose to advance more quickly or more slowly in most subject areas and could determine their own needs and progress. Many years later, Principal Catherine Misson further developed this philosophy of personal responsibility for learning, but now within a framework of lifelong health and wellbeing. The students were assisted to find a self-regulated commitment to study and exercise through independent learning times and greater freedom of decision making.

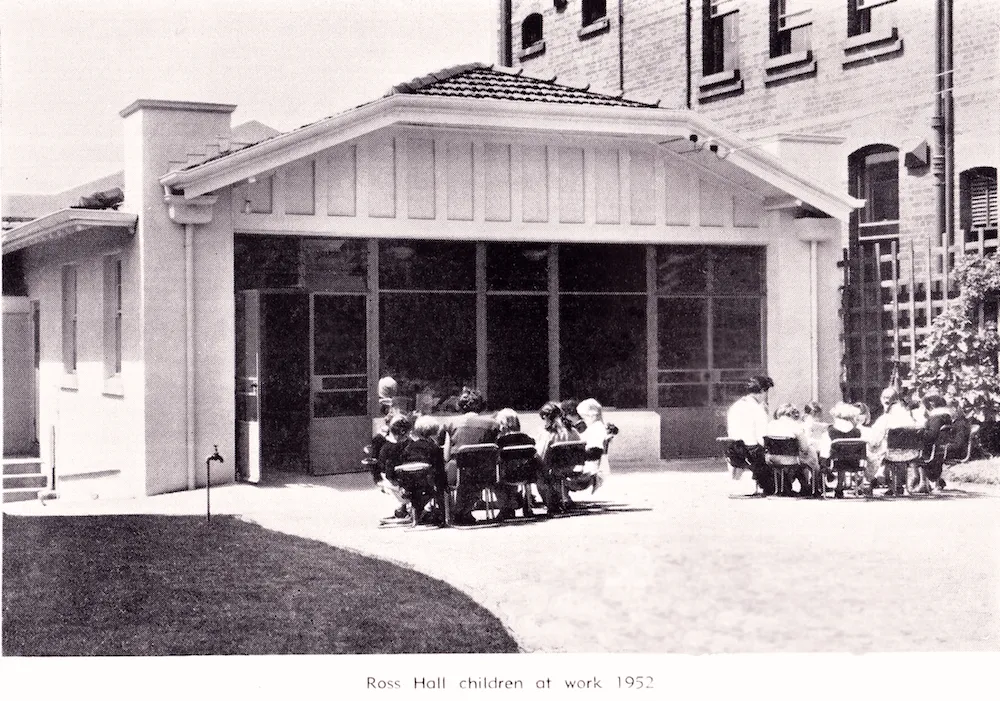

In the 1940s and ‘50s, Headmistress Miss DJ Ross built on Miss Gilman Jones’s innovative ideas, focusing attention on the way learning could be a co-operative effort between teachers and students. The Morris and Merton Hall classrooms were very different from those in most other schools. Tables and chairs were light and could be easily moved, so small discussion and work groups could readily form. Girls collaborated with each other, and the teacher was, at times, part of group discussions helping them to find their way to new understandings.

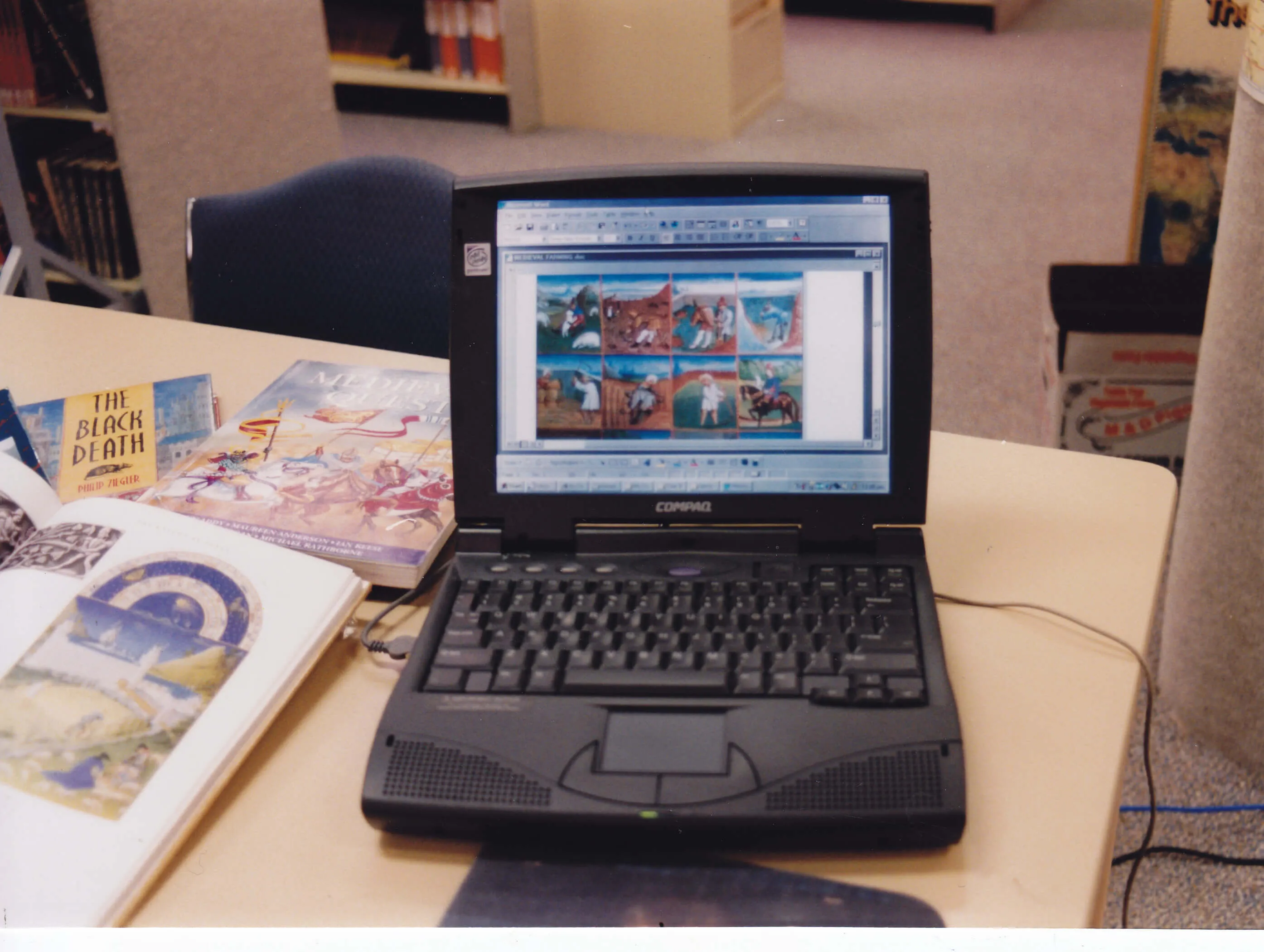

By the 1970s and ‘80s, the School cast its sights on the globalisation of education and the opportunities of looking beyond the red brick walls. Principal Nina Crone guided staff and students to an understanding of the place of MGGS, not just in Australia but in the world, with broader curriculum offerings, new languages for study, ground-breaking tours of China and student opportunities for travel to Europe and Asia. The students were learning that their future would be in a global world. By the 1990s, Principal Christine Briggs was ensuring that the girls had the vital technical skills to take part in a future digital world.

Today, we see the hallmarks of these great educationalists. Innovation, a future focus, creativity – in our School, these are not new words. They have been the pattern right from the start; they are a way of thinking and approaching education. Every era at MGGS has been able to look forward to the future needs of its student population, confident that they stand on solid educational foundations built by previous generations.

In 1925, Headmistress Miss Gilman Jones challenged the School to think about learning in a different way. She wanted the girls to take more responsibility and accountability for their own learning. Rather than traditional lock-step progression, she created a middle school, highly unusual for the 1920s and far ahead of its time. Grammarians became members of the three new houses, rather than of the traditional year levels and could chart their own progress across those years. They could choose to advance more quickly or more slowly in most subject areas and could determine their own needs and progress. Many years later, Principal Catherine Misson further developed this philosophy of personal responsibility for learning, but now within a framework of lifelong health and wellbeing. The students were assisted to find a self-regulated commitment to study and exercise through independent learning times and greater freedom of decision making.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, Headmistress Miss DJ Ross built on Miss Gilman Jones’s innovative ideas, focusing attention on the way learning could be a co-operative effort between teachers and students. The Morris and Merton Hall classrooms were very different from those in most other schools. Tables and chairs were light and could be easily moved, so small discussion and work groups could readily form. Girls collaborated with each other, and the teacher was, at times, part of group discussions helping them to find their way to new understandings.

By the 1970s and ‘80s, the School cast its sights on the globalisation of education and the opportunities of looking beyond the red brick walls. Principal Nina Crone guided staff and students to an understanding of the place of MGGS, not just in Australia but in the world, with broader curriculum offerings, new languages for study, ground-breaking tours of China and student opportunities for travel to Europe and Asia. The students were learning that their future would be in a global world. By the 1990s, Principal Christine Briggs was ensuring that the girls had the vital technical skills to take part in a future digital world.

Today, we see the hallmarks of these great educationalists. Innovation, a future focus, creativity – in our School, these are not new words. They have been the pattern right from the start; they are a way of thinking and approaching education. Every era at MGGS has been able to look forward to the future needs of its student population, confident that they stand on solid educational foundations built by previous generations.

-2.webp)