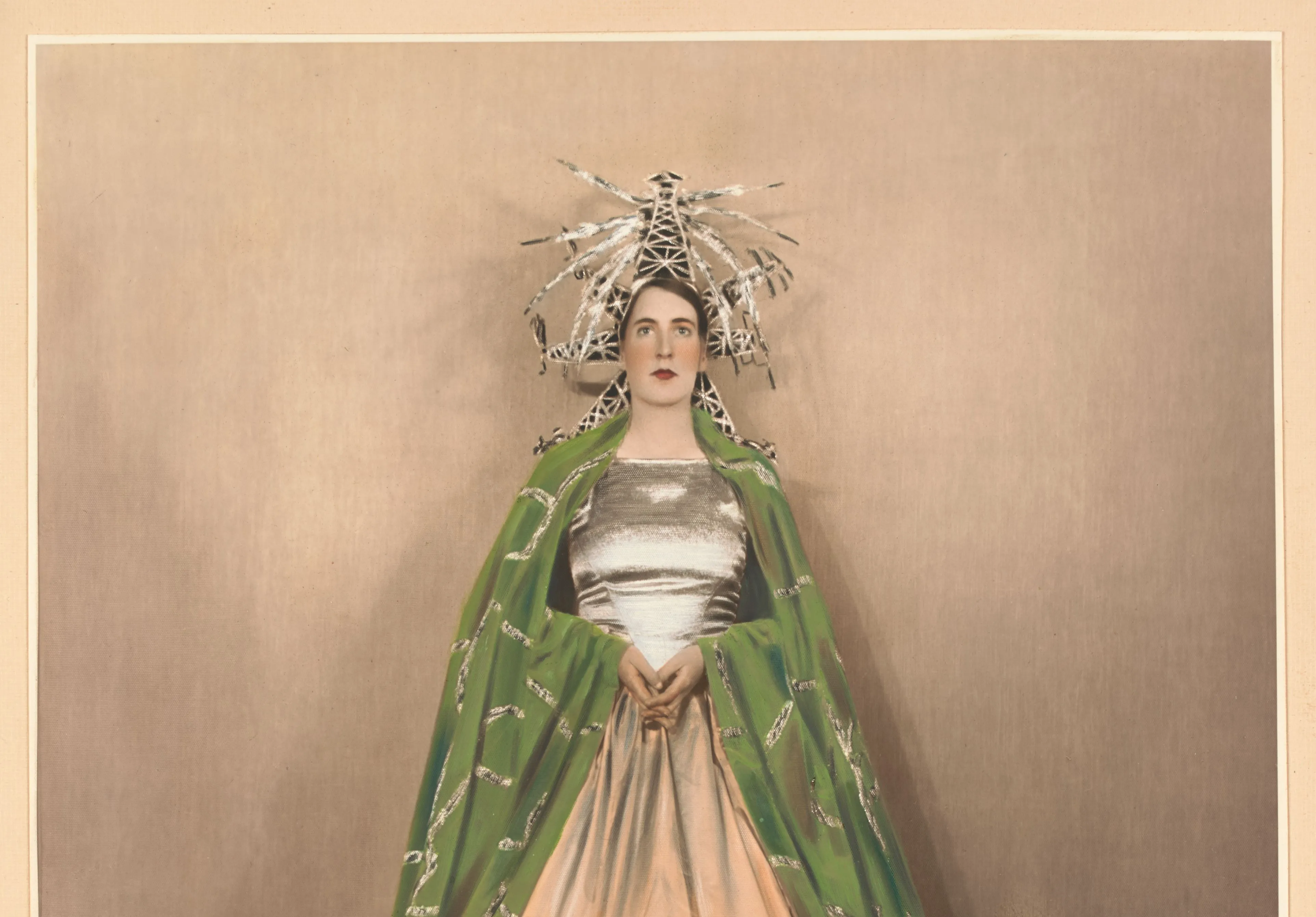

Old Grammarian Jessie Clarke (Brookes) as Queen Victoria in the 1935 Centenary Pageant: "Students in all schools were often conscripted, most quite willingly, to take part from time to time in public displays of imperial and nationalistic gravitas. As static tableaux displaying patriotic themes, pageants typically celebrated the 'natural order' of the British Empire and Australia's place within it."

Old Grammarian Jessie Clarke (Brookes) as Queen Victoria in the 1935 Centenary Pageant: "Students in all schools were often conscripted, most quite willingly, to take part from time to time in public displays of imperial and nationalistic gravitas. As static tableaux displaying patriotic themes, pageants typically celebrated the 'natural order' of the British Empire and Australia's place within it."

From Pagentry to Feminist Pioneers

This year we published a commemorative book, Lines of Flight, to mark our 130th anniversary. Written by author Adjunct Professor Erica McWilliam AM, Lines of Flight brings a new visibility to the times and inherent sensitivities that have shaped girls' education. In its pages, Melbourne Girls Grammar is investigated as a culturally specific site where the tension and contestation of progress has been illustrated through the colourful characters and sharp intellects that have graced its halls over the past one hundred and thirty years since its founding in 1893.

Below you will find an excerpt from Lines of Flight’s seventh chapter, 'Creative Spaces', which touches on creativity and the arts at the School across the years.

A key point to be made here is that, while music and drama have featured prominently in the work of the School since its inception, such offerings were never intended at that time as a springboard from which a girl might carve out a solo career. Genuine aptitude shown in any of the desirable feminine accomplishments was understood to be a potential embellishment to a future household, not a life’s work. As such, accomplishments did not require ‘the great good place’ – indeed, such a place was not only unnecessary, but undesirable. ‘Drawing’ would never be art; singing and piano-playing would never end in composing or conducting; a dancer would never anticipate membership of the corps de ballet; creative writing would never lead to recognition as an author, unless, like Henry Handel Richardson, the work was done under a male pseudonym; modern languages might enliven European travel, or allow a young woman to teach, but would not morph into a career as a linguist. In other words, training in ‘accomplishments’ ought not to be taken as synonymous with what might now be termed ‘creative capacity building’, but rather constituted a form of moral training designed to develop a girl’s skills and sensibilities in socially approved ways. Its purpose was to fit young women to their limited social role – to enable and constrain them simultaneously.

That said, the School can identify many exceptional creatives among its graduates since its earliest days, only a few of whom appear in this chapter. If girls were constrained in any significant way by their classroom days, as most school students have been one way or another, some were also enabled to spin out of the confines of domesticity into a space hitherto unoccupied, a space that inspired them to produce remarkable works of art and reach unprecedented heights in academe and on the sporting field. Among this group of exceptionally high achievers, many were supported through the resources and patronage of their well-to-do parents, a reminder that any number of “mute inglorious Miltons”[i] would have been prevented from achieving greatness because of their family’s constrained financial circumstances.

Financial pressures would soon be an issue for the newly established Merton Hall. A bank failure and resultant depression had really begun to bite in Melbourne by 1895, causing a dramatic change in the confidence and capacity of a city that had been flourishing, and along with it, a shift to economic pragmatism that saw any and all artistic endeavour take a backseat to agriculture, industry and commerce. The widespread decline in Victoria’s fortunes followed closely on the “optimism and excesses of the land boom”[ii] of the 1880s, during which time Melbourne’s artists had flourished. Purpose-built premises like Grosvenor Chambers had been constructed to accommodate the studios of many notable Melbourne painters, among whom one in particular, Arthur Streeton, had close links to the School.

Streeton moved from Melbourne to Sydney in the 1890s and thence overseas, returning to live beside the School in the 1920s, by which time his fame as a founding member of the Heidelberg School of Australian en plein air impressionists was well established. His sun-drenched painting, “View from the Hockey Field”,[iii] which hangs rather modestly in one of the School’s reception rooms, looks down from his studio in Fairlie House above the hockey field and then out across a Melbourne landscape that is much changed, unlike the reception room, which fortunately retains its thoroughly Edwardian character.

A key point to be made here is that, while music and drama have featured prominently in the work of the School since its inception, such offerings were never intended at that time as a springboard from which a girl might carve out a solo career. Genuine aptitude shown in any of the desirable feminine accomplishments was understood to be a potential embellishment to a future household, not a life’s work. As such, accomplishments did not require ‘the great good place’ – indeed, such a place was not only unnecessary, but undesirable. ‘Drawing’ would never be art; singing and piano-playing would never end in composing or conducting; a dancer would never anticipate membership of the corps de ballet; creative writing would never lead to recognition as an author, unless, like Henry Handel Richardson, the work was done under a male pseudonym; modern languages might enliven European travel, or allow a young woman to teach, but would not morph into a career as a linguist. In other words, training in ‘accomplishments’ ought not to be taken as synonymous with what might now be termed ‘creative capacity building’, but rather constituted a form of moral training designed to develop a girl’s skills and sensibilities in socially approved ways. Its purpose was to fit young women to their limited social role – to enable and constrain them simultaneously.

That said, the School can identify many exceptional creatives among its graduates since its earliest days, only a few of whom appear in this chapter. If girls were constrained in any significant way by their classroom days, as most school students have been one way or another, some were also enabled to spin out of the confines of domesticity into a space hitherto unoccupied, a space that inspired them to produce remarkable works of art and reach unprecedented heights in academe and on the sporting field. Among this group of exceptionally high achievers, many were supported through the resources and patronage of their well-to-do parents, a reminder that any number of “mute inglorious Miltons”[i] would have been prevented from achieving greatness because of their family’s constrained financial circumstances.

Financial pressures would soon be an issue for the newly established Merton Hall. A bank failure and resultant depression had really begun to bite in Melbourne by 1895, causing a dramatic change in the confidence and capacity of a city that had been flourishing, and along with it, a shift to economic pragmatism that saw any and all artistic endeavour take a backseat to agriculture, industry and commerce. The widespread decline in Victoria’s fortunes followed closely on the “optimism and excesses of the land boom”[ii] of the 1880s, during which time Melbourne’s artists had flourished. Purpose-built premises like Grosvenor Chambers had been constructed to accommodate the studios of many notable Melbourne painters, among whom one in particular, Arthur Streeton, had close links to the School.

Streeton moved from Melbourne to Sydney in the 1890s and thence overseas, returning to live beside the School in the 1920s, by which time his fame as a founding member of the Heidelberg School of Australian en plein air impressionists was well established. His sun-drenched painting, “View from the Hockey Field”,[iii] which hangs rather modestly in one of the School’s reception rooms, looks down from his studio in Fairlie House above the hockey field and then out across a Melbourne landscape that is much changed, unlike the reception room, which fortunately retains its thoroughly Edwardian character.

A key point to be made here is that, while music and drama have featured prominently in the work of the School since its inception, such offerings were never intended at that time as a springboard from which a girl might carve out a solo career. Genuine aptitude shown in any of the desirable feminine accomplishments was understood to be a potential embellishment to a future household, not a life’s work. As such, accomplishments did not require ‘the great good place’ – indeed, such a place was not only unnecessary, but undesirable. ‘Drawing’ would never be art; singing and piano-playing would never end in composing or conducting; a dancer would never anticipate membership of the corps de ballet; creative writing would never lead to recognition as an author, unless, like Henry Handel Richardson, the work was done under a male pseudonym; modern languages might enliven European travel, or allow a young woman to teach, but would not morph into a career as a linguist. In other words, training in ‘accomplishments’ ought not to be taken as synonymous with what might now be termed ‘creative capacity building’, but rather constituted a form of moral training designed to develop a girl’s skills and sensibilities in socially approved ways. Its purpose was to fit young women to their limited social role – to enable and constrain them simultaneously.

That said, the School can identify many exceptional creatives among its graduates since its earliest days, only a few of whom appear in this chapter. If girls were constrained in any significant way by their classroom days, as most school students have been one way or another, some were also enabled to spin out of the confines of domesticity into a space hitherto unoccupied, a space that inspired them to produce remarkable works of art and reach unprecedented heights in academe and on the sporting field. Among this group of exceptionally high achievers, many were supported through the resources and patronage of their well-to-do parents, a reminder that any number of “mute inglorious Miltons”[i] would have been prevented from achieving greatness because of their family’s constrained financial circumstances.

Financial pressures would soon be an issue for the newly established Merton Hall. A bank failure and resultant depression had really begun to bite in Melbourne by 1895, causing a dramatic change in the confidence and capacity of a city that had been flourishing, and along with it, a shift to economic pragmatism that saw any and all artistic endeavour take a backseat to agriculture, industry and commerce. The widespread decline in Victoria’s fortunes followed closely on the “optimism and excesses of the land boom”[ii] of the 1880s, during which time Melbourne’s artists had flourished. Purpose-built premises like Grosvenor Chambers had been constructed to accommodate the studios of many notable Melbourne painters, among whom one in particular, Arthur Streeton, had close links to the School.

Streeton moved from Melbourne to Sydney in the 1890s and thence overseas, returning to live beside the School in the 1920s, by which time his fame as a founding member of the Heidelberg School of Australian en plein air impressionists was well established. His sun-drenched painting, “View from the Hockey Field”,[iii] which hangs rather modestly in one of the School’s reception rooms, looks down from his studio in Fairlie House above the hockey field and then out across a Melbourne landscape that is much changed, unlike the reception room, which fortunately retains its thoroughly Edwardian character.

Old Grammarian Clarice Beckett spent three years under Fredrick McCubbin’s tuition, just as Hilda Rix had done, but her parents’ ill health and reduced circumstances saw her prodigious talent delimited in time and opportunity by her role as their full-time carer.

Old Grammarian Clarice Beckett spent three years under Fredrick McCubbin’s tuition, just as Hilda Rix had done, but her parents’ ill health and reduced circumstances saw her prodigious talent delimited in time and opportunity by her role as their full-time carer.

If there was one positive to come from the depressed economy of the 1890s – and again in the 1930s – it was the greater availability of studio space made possible through a drop in rental prices. However, much of the housing on offer was a far cry from the lavish interiors of studios that characterised the artistic heyday of Melbourne in the late 1880s. And if Melbourne’s notable male artists were finding the going heavy, the times were harder still for its creative women, few of whom were being taken seriously as capable, cutting-edge innovators.

It is not difficult, given the reduced circumstances of ‘creatives’ following the depression of the early 1890s, to see the appeal of Paris and London as destinations for aspiring young artists, both male and female. George du Maurier’s best-selling serial publication, Trilby, appeared in 1894 at the precise historical moment when artistic communities seemed to be in decline.[iv] Published as a novel in 1895, Trilby caused a sensation with its enticing romantic tale of bohemian studio life in Paris. Du Maurier depicted the ‘true’ fin-de-siècle artistic lifestyle as idyllic – an aesthetically and artistically vibrant way of living that was blissfully independent of wealth or social status. Bohemianism was a romance that was particularly attractive to artists seeking a community of likeminded others, but it was also a lifestyle more available to men than to women, the latter always already constrained in their lifestyle choices by the separate spheres in which men and women lived and worked. Only a ‘certain kind of woman’ plays a part in Bohemia – models, muses, lovers. Moreover, the parts they played were morally questionable and eminently dispensable. In sum, the studio life might have been seductive as an artistic ideal, but it remained mostly off-limits to the daughters of the respectable middle-class parents who enrolled their daughters in private girls’ schools like Merton Hall.

There was, however, safety in pageants. Students in all schools were often conscripted, most quite willingly, to take part from time to time in public displays of imperial and nationalistic gravitas. As static tableaux displaying patriotic themes, pageants typically celebrated the ‘natural order’ of the British Empire and Australia’s place within it, and as such they were very popular indeed during the Great War. Their popularity continued well into the 1930s, as is evidenced in the glowing – indeed, hyperbolic – tributes given to a typical pageant performed by the International Club of Victoria in 1935. It was, according to the Argus, “a remarkable achievement on the part of the International Club of Victoria” in bringing together the national communities of Melbourne in “a gesture of friendliness and congratulation to the State of Victoria on the celebration of its 100th year”.[v] Jessie Deakin Brookes, who had recently graduated from the School, had a major role as Queen Victoria, appropriately attired in regal costume. It was a scene, gushed the reportage, that “increased in beauty and splendour as nation followed nation and the groups were massed on the stage, presenting a kaleidoscope of colour and an impression of magnificence that were beyond description.” A description followed, nevertheless:

Exquisite in its colouring was Victoria’s gown. With a bodice of cloth of silver and a crinoline skirt of golden maize satin, the hem painted delicately in green to suggest the skyline of Melbourne, and a wonderful velvet cloak of burgeoning green, traced with silver to symbolize the fertility of the irrigated lands, the costume was completed by a marvellous headdress of scintillating silver … The whole effect was superb.[vi]

Pageants reassured participants and audiences that all was right with the grand narrative of British heritage – that its hierarchies were durable, respectable and virtuous. Pageantry’s tidying imperative, while popular when national rally-points were needed, ran directly counter to the lure of bohemianism. The nobly swathed women ‘standing in’ for queen and country with dignified silence were as far, symbolically, from the half-naked artist model as it was possible to get.

Melbourne’s governors, however, did acknowledge that some women were speaking with a stronger voice of their own in a new century. Soon after Federation, the capital of the new nation had begun to earn a strong reputation for its ‘social laboratory’ progressivism. Indeed, the first Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work, held in Melbourne in October 1907, was unique in its time for the trust placed in the capacity of a display of women’s arts and crafts to attract an international audience over an extended period of time. It could also be argued, as Kristin Otto points out, that Melbourne had begun moving in very fundamental ways to acknowledge and accommodate its female citizens, installing the first publicly available women’s underground lavatories in Russell Street in 1902, and following South Australia’s lead by granting non-Indigenous women the vote. Moreover, one of Melbourne’s most eminent and influential citizens, Janet Lady Clarke, was in her time the richest woman in Australia and the creator of both cricket’s best-known trophy, The Ashes, and the Australian Women's National League.[vii]

If there was one positive to come from the depressed economy of the 1890s – and again in the 1930s – it was the greater availability of studio space made possible through a drop in rental prices. However, much of the housing on offer was a far cry from the lavish interiors of studios that characterised the artistic heyday of Melbourne in the late 1880s. And if Melbourne’s notable male artists were finding the going heavy, the times were harder still for its creative women, few of whom were being taken seriously as capable, cutting-edge innovators.

It is not difficult, given the reduced circumstances of ‘creatives’ following the depression of the early 1890s, to see the appeal of Paris and London as destinations for aspiring young artists, both male and female. George du Maurier’s best-selling serial publication, Trilby, appeared in 1894 at the precise historical moment when artistic communities seemed to be in decline.[iv] Published as a novel in 1895, Trilby caused a sensation with its enticing romantic tale of bohemian studio life in Paris. Du Maurier depicted the ‘true’ fin-de-siècle artistic lifestyle as idyllic – an aesthetically and artistically vibrant way of living that was blissfully independent of wealth or social status. Bohemianism was a romance that was particularly attractive to artists seeking a community of likeminded others, but it was also a lifestyle more available to men than to women, the latter always already constrained in their lifestyle choices by the separate spheres in which men and women lived and worked. Only a ‘certain kind of woman’ plays a part in Bohemia – models, muses, lovers. Moreover, the parts they played were morally questionable and eminently dispensable. In sum, the studio life might have been seductive as an artistic ideal, but it remained mostly off-limits to the daughters of the respectable middle-class parents who enrolled their daughters in private girls’ schools like Merton Hall.

There was, however, safety in pageants. Students in all schools were often conscripted, most quite willingly, to take part from time to time in public displays of imperial and nationalistic gravitas. As static tableaux displaying patriotic themes, pageants typically celebrated the ‘natural order’ of the British Empire and Australia’s place within it, and as such they were very popular indeed during the Great War. Their popularity continued well into the 1930s, as is evidenced in the glowing – indeed, hyperbolic – tributes given to a typical pageant performed by the International Club of Victoria in 1935. It was, according to the Argus, “a remarkable achievement on the part of the International Club of Victoria” in bringing together the national communities of Melbourne in “a gesture of friendliness and congratulation to the State of Victoria on the celebration of its 100th year”.[v] Jessie Deakin Brookes, who had recently graduated from the School, had a major role as Queen Victoria, appropriately attired in regal costume. It was a scene, gushed the reportage, that “increased in beauty and splendour as nation followed nation and the groups were massed on the stage, presenting a kaleidoscope of colour and an impression of magnificence that were beyond description.” A description followed, nevertheless:

Exquisite in its colouring was Victoria’s gown. With a bodice of cloth of silver and a crinoline skirt of golden maize satin, the hem painted delicately in green to suggest the skyline of Melbourne, and a wonderful velvet cloak of burgeoning green, traced with silver to symbolize the fertility of the irrigated lands, the costume was completed by a marvellous headdress of scintillating silver … The whole effect was superb.[vi]

Pageants reassured participants and audiences that all was right with the grand narrative of British heritage – that its hierarchies were durable, respectable and virtuous. Pageantry’s tidying imperative, while popular when national rally-points were needed, ran directly counter to the lure of bohemianism. The nobly swathed women ‘standing in’ for queen and country with dignified silence were as far, symbolically, from the half-naked artist model as it was possible to get.

Melbourne’s governors, however, did acknowledge that some women were speaking with a stronger voice of their own in a new century. Soon after Federation, the capital of the new nation had begun to earn a strong reputation for its ‘social laboratory’ progressivism. Indeed, the first Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work, held in Melbourne in October 1907, was unique in its time for the trust placed in the capacity of a display of women’s arts and crafts to attract an international audience over an extended period of time. It could also be argued, as Kristin Otto points out, that Melbourne had begun moving in very fundamental ways to acknowledge and accommodate its female citizens, installing the first publicly available women’s underground lavatories in Russell Street in 1902, and following South Australia’s lead by granting non-Indigenous women the vote. Moreover, one of Melbourne’s most eminent and influential citizens, Janet Lady Clarke, was in her time the richest woman in Australia and the creator of both cricket’s best-known trophy, The Ashes, and the Australian Women's National League.[vii]

If there was one positive to come from the depressed economy of the 1890s – and again in the 1930s – it was the greater availability of studio space made possible through a drop in rental prices. However, much of the housing on offer was a far cry from the lavish interiors of studios that characterised the artistic heyday of Melbourne in the late 1880s. And if Melbourne’s notable male artists were finding the going heavy, the times were harder still for its creative women, few of whom were being taken seriously as capable, cutting-edge innovators.

It is not difficult, given the reduced circumstances of ‘creatives’ following the depression of the early 1890s, to see the appeal of Paris and London as destinations for aspiring young artists, both male and female. George du Maurier’s best-selling serial publication, Trilby, appeared in 1894 at the precise historical moment when artistic communities seemed to be in decline.[iv] Published as a novel in 1895, Trilby caused a sensation with its enticing romantic tale of bohemian studio life in Paris. Du Maurier depicted the ‘true’ fin-de-siècle artistic lifestyle as idyllic – an aesthetically and artistically vibrant way of living that was blissfully independent of wealth or social status. Bohemianism was a romance that was particularly attractive to artists seeking a community of likeminded others, but it was also a lifestyle more available to men than to women, the latter always already constrained in their lifestyle choices by the separate spheres in which men and women lived and worked. Only a ‘certain kind of woman’ plays a part in Bohemia – models, muses, lovers. Moreover, the parts they played were morally questionable and eminently dispensable. In sum, the studio life might have been seductive as an artistic ideal, but it remained mostly off-limits to the daughters of the respectable middle-class parents who enrolled their daughters in private girls’ schools like Merton Hall.

There was, however, safety in pageants. Students in all schools were often conscripted, most quite willingly, to take part from time to time in public displays of imperial and nationalistic gravitas. As static tableaux displaying patriotic themes, pageants typically celebrated the ‘natural order’ of the British Empire and Australia’s place within it, and as such they were very popular indeed during the Great War. Their popularity continued well into the 1930s, as is evidenced in the glowing – indeed, hyperbolic – tributes given to a typical pageant performed by the International Club of Victoria in 1935. It was, according to the Argus, “a remarkable achievement on the part of the International Club of Victoria” in bringing together the national communities of Melbourne in “a gesture of friendliness and congratulation to the State of Victoria on the celebration of its 100th year”.[v] Jessie Deakin Brookes, who had recently graduated from the School, had a major role as Queen Victoria, appropriately attired in regal costume. It was a scene, gushed the reportage, that “increased in beauty and splendour as nation followed nation and the groups were massed on the stage, presenting a kaleidoscope of colour and an impression of magnificence that were beyond description.” A description followed, nevertheless:

Exquisite in its colouring was Victoria’s gown. With a bodice of cloth of silver and a crinoline skirt of golden maize satin, the hem painted delicately in green to suggest the skyline of Melbourne, and a wonderful velvet cloak of burgeoning green, traced with silver to symbolize the fertility of the irrigated lands, the costume was completed by a marvellous headdress of scintillating silver … The whole effect was superb.[vi]

Pageants reassured participants and audiences that all was right with the grand narrative of British heritage – that its hierarchies were durable, respectable and virtuous. Pageantry’s tidying imperative, while popular when national rally-points were needed, ran directly counter to the lure of bohemianism. The nobly swathed women ‘standing in’ for queen and country with dignified silence were as far, symbolically, from the half-naked artist model as it was possible to get.

Melbourne’s governors, however, did acknowledge that some women were speaking with a stronger voice of their own in a new century. Soon after Federation, the capital of the new nation had begun to earn a strong reputation for its ‘social laboratory’ progressivism. Indeed, the first Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work, held in Melbourne in October 1907, was unique in its time for the trust placed in the capacity of a display of women’s arts and crafts to attract an international audience over an extended period of time. It could also be argued, as Kristin Otto points out, that Melbourne had begun moving in very fundamental ways to acknowledge and accommodate its female citizens, installing the first publicly available women’s underground lavatories in Russell Street in 1902, and following South Australia’s lead by granting non-Indigenous women the vote. Moreover, one of Melbourne’s most eminent and influential citizens, Janet Lady Clarke, was in her time the richest woman in Australia and the creator of both cricket’s best-known trophy, The Ashes, and the Australian Women's National League.[vii]

Old Grammarian Hilda Rix: “As an early member of the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors, Rix was as well placed as any exceptionally gifted woman to make a successful career as a Melbourne artist.”

Old Grammarian Hilda Rix: “As an early member of the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors, Rix was as well placed as any exceptionally gifted woman to make a successful career as a Melbourne artist.”

Notwithstanding Melbourne’s relatively progressive policies on behalf of women, more than one young graduate from the School chose instead to depart from Melbourne and set sail for the art studios of Paris. In 1907, the very year that the Women’s Exhibition was in full swing, the brilliant Hilda Rix, after taking painting lessons at the School, and subsequently studying for three years under the impressionist Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, booked a passage to Europe with her mother and her sister Elsie. Rix had the exceptional talent – as well as the means and the opportunity – to be much more than an artist’s apprentice. Born of wealthy and devoted parents, and without any brothers with whom to compete for parental patronage, Rix took her place among “that glorious generation of early 20th century women artists …[who] were the daughters of the first women to be given some kind of formal education [and] ... the daughters of the first women to own property after marriage.”[viii] Joanna Mendelssohn elaborates:

In a very real sense these women, often portrayed as feminist pioneers, were the first beneficiaries of an older generation of feminists. When Hilda Rix travelled abroad to study art, she did so both with family, and with family support. She was encouraged to make art, and her illustrative style, first demonstrated when she was a student, continued through her maturity.[ix]

It would seem fair to include the School’s first headmistresses, Emily Hensley and Alice Taylor, and their successors Edith and Mary Morris, among the “feminist pioneers” who launched young women like Rix into a new and exciting world of creative endeavour. The descriptor “feminist” as applied here should not be taken as implying some leftist political leaning but rather as denoting one facet of a more complex identity formation – that of “politically conservative Australian nationalist feminist”.[x] This multi-faceted descriptor of Rix’s life trajectory could well apply to any number of Old Grammarians who went on to make their indelible mark on a wider social and cultural world.

Notwithstanding Melbourne’s relatively progressive policies on behalf of women, more than one young graduate from the School chose instead to depart from Melbourne and set sail for the art studios of Paris. In 1907, the very year that the Women’s Exhibition was in full swing, the brilliant Hilda Rix, after taking painting lessons at the School, and subsequently studying for three years under the impressionist Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, booked a passage to Europe with her mother and her sister Elsie. Rix had the exceptional talent – as well as the means and the opportunity – to be much more than an artist’s apprentice. Born of wealthy and devoted parents, and without any brothers with whom to compete for parental patronage, Rix took her place among “that glorious generation of early 20th century women artists …[who] were the daughters of the first women to be given some kind of formal education [and] ... the daughters of the first women to own property after marriage.”[viii] Joanna Mendelssohn elaborates:

In a very real sense these women, often portrayed as feminist pioneers, were the first beneficiaries of an older generation of feminists. When Hilda Rix travelled abroad to study art, she did so both with family, and with family support. She was encouraged to make art, and her illustrative style, first demonstrated when she was a student, continued through her maturity.[ix]

It would seem fair to include the School’s first headmistresses, Emily Hensley and Alice Taylor, and their successors Edith and Mary Morris, among the “feminist pioneers” who launched young women like Rix into a new and exciting world of creative endeavour. The descriptor “feminist” as applied here should not be taken as implying some leftist political leaning but rather as denoting one facet of a more complex identity formation – that of “politically conservative Australian nationalist feminist”.[x] This multi-faceted descriptor of Rix’s life trajectory could well apply to any number of Old Grammarians who went on to make their indelible mark on a wider social and cultural world.

Notwithstanding Melbourne’s relatively progressive policies on behalf of women, more than one young graduate from the School chose instead to depart from Melbourne and set sail for the art studios of Paris. In 1907, the very year that the Women’s Exhibition was in full swing, the brilliant Hilda Rix, after taking painting lessons at the School, and subsequently studying for three years under the impressionist Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, booked a passage to Europe with her mother and her sister Elsie. Rix had the exceptional talent – as well as the means and the opportunity – to be much more than an artist’s apprentice. Born of wealthy and devoted parents, and without any brothers with whom to compete for parental patronage, Rix took her place among “that glorious generation of early 20th century women artists …[who] were the daughters of the first women to be given some kind of formal education [and] ... the daughters of the first women to own property after marriage.”[viii] Joanna Mendelssohn elaborates:

In a very real sense these women, often portrayed as feminist pioneers, were the first beneficiaries of an older generation of feminists. When Hilda Rix travelled abroad to study art, she did so both with family, and with family support. She was encouraged to make art, and her illustrative style, first demonstrated when she was a student, continued through her maturity.[ix]

It would seem fair to include the School’s first headmistresses, Emily Hensley and Alice Taylor, and their successors Edith and Mary Morris, among the “feminist pioneers” who launched young women like Rix into a new and exciting world of creative endeavour. The descriptor “feminist” as applied here should not be taken as implying some leftist political leaning but rather as denoting one facet of a more complex identity formation – that of “politically conservative Australian nationalist feminist”.[x] This multi-faceted descriptor of Rix’s life trajectory could well apply to any number of Old Grammarians who went on to make their indelible mark on a wider social and cultural world.

If this excerpt has piqued your curiosity and you would like to read more, you can order Lines of Flight on this page https://www.mggs.vic.edu.au/lines-of-flight

[i] Gray, Thomas (1750) “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44299/elegy-written-in-a-country-churchyard accessed 24 July 2021.

[ii] https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00460b.htm, accessed 14 February 2021.

[iii] ‘View from the Hockey Field’ was selected, appropriately, as the front cover for the School’s centenary publication, Centenary Essays, 1893-1993. (1993) Rosslyn McCarthy and Marjorie Theobald (Eds), Melbourne: Hyland House.

[iv] Du Maurier, George (1895) Trilby. London: Osgood, McIlvaine.

[v] Soumilas, Annette (2018) ‘I was the State of Victoria’: Jessie Clarke’s 1934 Pageant of Nations costume, LaTrobe Journal No.102, p.80.

[vi] Ibid, p.80.

[vii] Otto, Kristin (2009) Capital: Melbourne When it was the Capital City of Australia, 1901-27. Melbourne: Text Publishing pp.71-76.

[viii] Mendelssohn, Joanna (2000) ‘Book Review, Hilda Rix Nicholas: Her Life and Her Art by John Pigot’, Artlink, https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/2488/hilda-rix-nicholas-her-life-and-her-art-by-john-pi/, accessed 8 February 2021.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

If this excerpt has piqued your curiosity and you would like to read more, you can order Lines of Flight on this page https://www.mggs.vic.edu.au/lines-of-flight

[i] Gray, Thomas (1750) “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44299/elegy-written-in-a-country-churchyard accessed 24 July 2021.

[ii] https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00460b.htm, accessed 14 February 2021.

[iii] ‘View from the Hockey Field’ was selected, appropriately, as the front cover for the School’s centenary publication, Centenary Essays, 1893-1993. (1993) Rosslyn McCarthy and Marjorie Theobald (Eds), Melbourne: Hyland House.

[iv] Du Maurier, George (1895) Trilby. London: Osgood, McIlvaine.

[v] Soumilas, Annette (2018) ‘I was the State of Victoria’: Jessie Clarke’s 1934 Pageant of Nations costume, LaTrobe Journal No.102, p.80.

[vi] Ibid, p.80.

[vii] Otto, Kristin (2009) Capital: Melbourne When it was the Capital City of Australia, 1901-27. Melbourne: Text Publishing pp.71-76.

[viii] Mendelssohn, Joanna (2000) ‘Book Review, Hilda Rix Nicholas: Her Life and Her Art by John Pigot’, Artlink, https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/2488/hilda-rix-nicholas-her-life-and-her-art-by-john-pi/, accessed 8 February 2021.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

.jpg)

.webp)