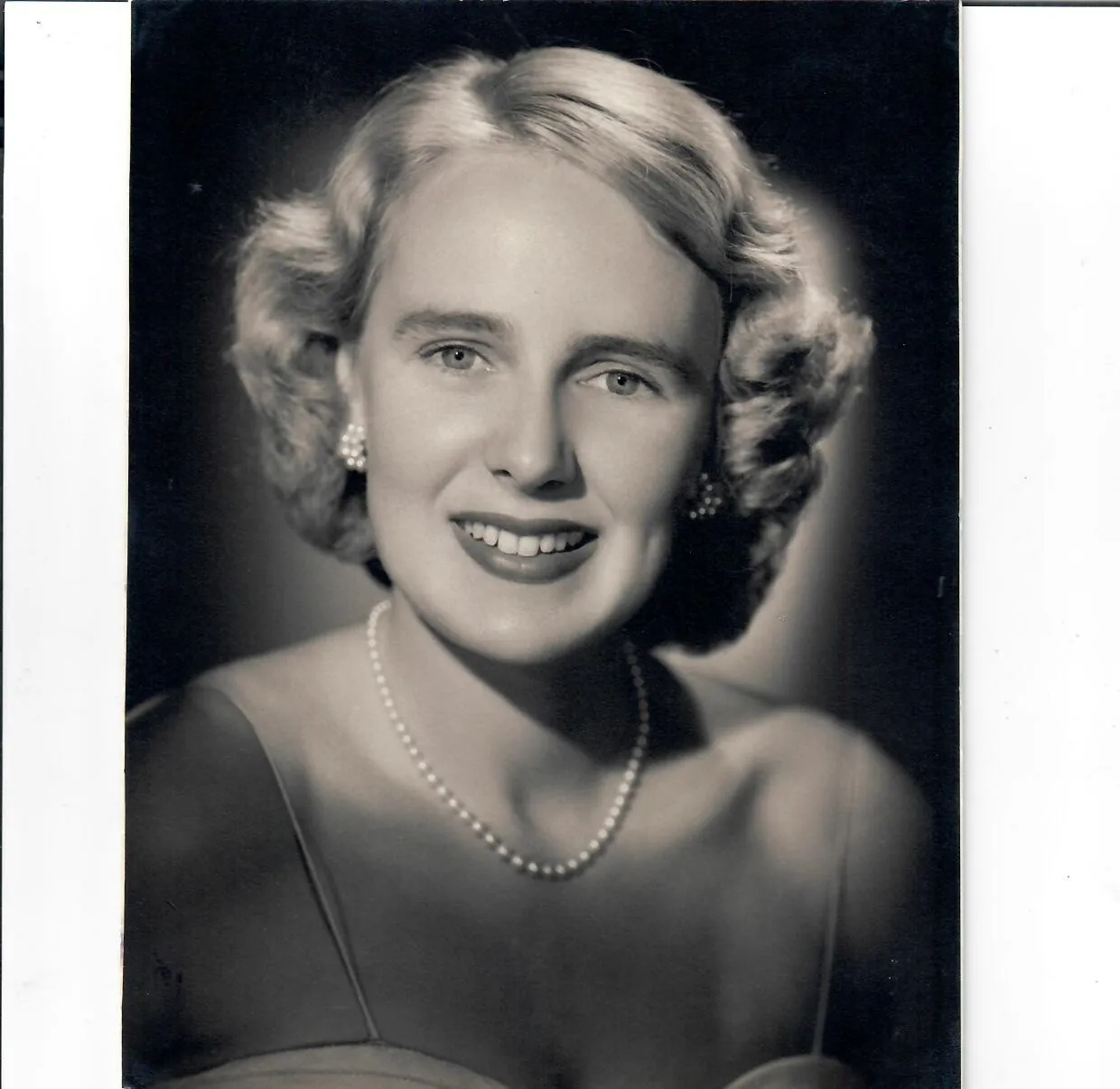

Greer Jalland (2005)

Greer Jalland (2005)

Beyond our Red Brick Walls

What does the future hold for our Grammarians beyond our red brick walls?

In this edition, we are delighted to introduce you to Old Grammarians Greer Jalland (2005) and Tessa Millington (2023) who, through their own unique pathways, have demonstrated the joy and reward that comes from service and generosity in different communities.

We hope you enjoy reading about their stories so far.

Greer Jalland (2005)

There wasn’t a specific moment when Greer Jalland (2005) decided to become a doctor. It was more of a slow, persistent feeling – one that began quietly and refused to let go.

Arriving at Melbourne Girls Grammar from Bendigo, Greer was a boarder and immersed herself into creative subjects, drama and sport. “I was probably more of a social butterfly than an academic. I loved the sports. I loved drama. I did the School production every year without fail. I just think Merton Hall was such a great school for fostering everybody's unique talents and strengths.”

Community service was a big part of school life at Melbourne Girls Grammar, but it was the Kokoda Trail trek in Year 10 that really stayed with her. “That trip to Papua New Guinea was a turning point for me. It made me think more deeply about privilege. About what it means to have access to education, safety, opportunity, and how I might use that well.”

In her early twenties, Greer was working in property and construction at Jones Lang LaSalle after finishing her degree in Urban Planning and Development at the University of Melbourne. On paper, it made sense. She’d always loved design, architecture, and how places are built, but she found herself craving more connection and purpose.

“As I got older and travelled more, I started questioning it. Sitting at a desk didn’t feel like enough. I loved people, talking to them, hearing their stories. I began wondering about medicine.”

In 2015, at 27 years old, she successfully sat the GAMSAT and was accepted into an undergraduate medical degree at Notre Dame University in Fremantle, Western Australia, where she embraced the training. While studying there, she met her husband, Joe, and together they had their first child. Greer started working as a junior doctor before having her second son. She completed rotations in psychiatry and realised she really enjoyed it. “I found that work really rewarding. So, my husband and I decided, we had our kids, why don't we do something different? We thought, well, why not give the Kimberley a go?”

Greer Jalland (2005)

There wasn’t a specific moment when Greer Jalland (2005) decided to become a doctor. It was more of a slow, persistent feeling – one that began quietly and refused to let go.

Arriving at Melbourne Girls Grammar from Bendigo, Greer was a boarder and immersed herself into creative subjects, drama and sport. “I was probably more of a social butterfly than an academic. I loved the sports. I loved drama. I did the School production every year without fail. I just think Merton Hall was such a great school for fostering everybody's unique talents and strengths.”

Community service was a big part of school life at Melbourne Girls Grammar, but it was the Kokoda Trail trek in Year 10 that really stayed with her. “That trip to Papua New Guinea was a turning point for me. It made me think more deeply about privilege. About what it means to have access to education, safety, opportunity, and how I might use that well.”

In her early twenties, Greer was working in property and construction at Jones Lang LaSalle after finishing her degree in Urban Planning and Development at the University of Melbourne. On paper, it made sense. She’d always loved design, architecture, and how places are built, but she found herself craving more connection and purpose.

“As I got older and travelled more, I started questioning it. Sitting at a desk didn’t feel like enough. I loved people, talking to them, hearing their stories. I began wondering about medicine.”

In 2015, at 27 years old, she successfully sat the GAMSAT and was accepted into an undergraduate medical degree at Notre Dame University in Fremantle, Western Australia, where she embraced the training. While studying there, she met her husband, Joe, and together they had their first child. Greer started working as a junior doctor before having her second son. She completed rotations in psychiatry and realised she really enjoyed it. “I found that work really rewarding. So, my husband and I decided, we had our kids, why don't we do something different? We thought, well, why not give the Kimberley a go?”

Greer Jalland (2005)

There wasn’t a specific moment when Greer Jalland (2005) decided to become a doctor. It was more of a slow, persistent feeling – one that began quietly and refused to let go.

Arriving at Melbourne Girls Grammar from Bendigo, Greer was a boarder and immersed herself into creative subjects, drama and sport. “I was probably more of a social butterfly than an academic. I loved the sports. I loved drama. I did the School production every year without fail. I just think Merton Hall was such a great school for fostering everybody's unique talents and strengths.”

Community service was a big part of school life at Melbourne Girls Grammar, but it was the Kokoda Trail trek in Year 10 that really stayed with her. “That trip to Papua New Guinea was a turning point for me. It made me think more deeply about privilege. About what it means to have access to education, safety, opportunity, and how I might use that well.”

In her early twenties, Greer was working in property and construction at Jones Lang LaSalle after finishing her degree in Urban Planning and Development at the University of Melbourne. On paper, it made sense. She’d always loved design, architecture, and how places are built, but she found herself craving more connection and purpose.

“As I got older and travelled more, I started questioning it. Sitting at a desk didn’t feel like enough. I loved people, talking to them, hearing their stories. I began wondering about medicine.”

In 2015, at 27 years old, she successfully sat the GAMSAT and was accepted into an undergraduate medical degree at Notre Dame University in Fremantle, Western Australia, where she embraced the training. While studying there, she met her husband, Joe, and together they had their first child. Greer started working as a junior doctor before having her second son. She completed rotations in psychiatry and realised she really enjoyed it. “I found that work really rewarding. So, my husband and I decided, we had our kids, why don't we do something different? We thought, well, why not give the Kimberley a go?”

Greer and her family in WA

Greer and her family in WA

So, four years ago, the family moved to up to the Kimberley and are now based in Broome, with Greer working predominantly in the hospital and in Community Mental Health. She began in the emergency department and then in a 14-bed inpatient psychiatric unit – one of the most isolated psychiatric wards anywhere in the world. Around 70% of Greer’s patients are from Aboriginal backgrounds.

“I look after the whole of the Kimberley, basically. From the Pilbara to the Northern Territory border, right up to Kununurra and a remote community called Kalumburu in the East Kimberley. So, it's a really vast area. A very isolated and remote area. You know it's isolated when it takes four days to drive to Perth from here and 18 hours to get to Darwin.”

“I have just found it fascinating working, learning about Aboriginal culture and way of life and bush medicine, language and culture. My job takes me to Aboriginal communities; I take light planes out to remote communities. I go to the Dampier Peninsula, One Arm Point, and another Aboriginal community called Bidyadanga, which is Australia’s largest Aboriginal community – about two and a half hours south of Broome, with about 850 residents. I also travel to Derby, Fitzroy Crossing and Halls Creek.” Her work often involves co-ordinating with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“We treat patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety. If someone becomes unwell in a remote community with psychosis, mania or suicidal ideation, we stabilise them, give them medication, and try to get them to Broome. Some communities have tiny clinics, with only one room. We might have to keep someone safe there for days, even a week, if there are no psychiatric beds available in the state.”

“I'm always supported by an Aboriginal Liaison Officer. I work very closely alongside Aboriginal mental health workers, so often they are adept in local language. The Kimberley is a really interesting place because there are 30 different languages here and different ‘skin groups’ in the community. The Yawuru people live in Broome. So that language is not always going to apply to someone that lives in Fitzroy Crossing. They'll have their own culture and language. Understanding those different nuances is interesting, as often English is their third language.”

Greer’s work involves the kind of medicine where every skill matters, and she has also developed a deep interest in transcultural psychiatry. “You become a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. It’s very different from working in the city. There, people might see prestige in being at a major centre. But up here, you learn to do so much with so little – and get great outcomes. I just really enjoy working in a remote setting, there’s a rawness to it – and a respect for what doctors can do with limited resources.” Sometimes, reviews take place not in clinics, but on ovals, at fishing spots, or in the back of a bus.

“It’s opportunistic medicine,” she says, smiling. “You take the moment when it comes.”

“We work closely with Aboriginal mental health workers and with families. Sometimes a family will ask for a healer to come, this is known as a ‘maban man’. That’s part of their understanding of health and spirituality, and we respect that. We also incorporate bush medicine, too. If someone has a bush remedy they take at night, we include it on their medication chart like any other prescription. You always respect and integrate the culture into your treatment plan. It’s about listening. It’s about trust.”

Alongside her professional life, she and her husband Joe, a GP, are raising their, now three, children. Remote life has its challenges: long hours, few amenities, limited childcare and distance from extended family. “If I want to visit my parents in Bendigo or go to Melbourne, travel takes a long time, and it’s expensive. But the kids are having a great time. They’re learning outside, they’re part of the local surf lifesaving club and Auskick. My husband loves camping. It’s a different kind of childhood – but a good one. In the schools here they are learning some of the local Aboriginal language, called Yawuru, which is lovely.’

“It’s not always easy. But it’s a beautiful life. You work in a job that means something. And you never forget how lucky you are to be here, doing this. It was fascinating to me at the time. I think once you see these places, once you begin to understand even a little of the complexity – you're changed. You want to learn more and do more.”

The problems faced in these remote communities are numerous. Substance misuse, generational trauma, high suicide rates, lack of access to an acute mental health bed ... There's a lot of domestic violence, unfortunately, which is something that communities are working hard to combat.” However, the people she has met show resilience, and the communities support one another. “Unfortunately, the Kimberley has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. So, you're often working with families, a lot of whom have had family members who have died by suicide. So, I’m very aware of that.”

Greer is still deciding which area of psychiatry to pursue long-term, child and adolescent, forensics or transcultural mental health, but she wants to keep returning to the Kimberley. “Even when I become a consultant psychiatrist, I imagine I’ll still come back once a month for a week, to consult, to give back. I feel a real connection to this place.”

“It's very unique. Although it's hard, I still think I wouldn't change it for the world and I'm really enjoying being up here, although it can be very isolating. It does make you value everything that you have. There’s a saying up north: ‘The red pindan dirt of the Kimberley gets under your skin’. I never thought I’d be that type of person,” she says, smiling. “But I absolutely love it. And I know I’ll always come back.”

So, four years ago, the family moved to up to the Kimberley and are now based in Broome, with Greer working predominantly in the hospital and in Community Mental Health. She began in the emergency department and then in a 14-bed inpatient psychiatric unit – one of the most isolated psychiatric wards anywhere in the world. Around 70% of Greer’s patients are from Aboriginal backgrounds.

“I look after the whole of the Kimberley, basically. From the Pilbara to the Northern Territory border, right up to Kununurra and a remote community called Kalumburu in the East Kimberley. So, it's a really vast area. A very isolated and remote area. You know it's isolated when it takes four days to drive to Perth from here and 18 hours to get to Darwin.”

“I have just found it fascinating working, learning about Aboriginal culture and way of life and bush medicine, language and culture. My job takes me to Aboriginal communities; I take light planes out to remote communities. I go to the Dampier Peninsula, One Arm Point, and another Aboriginal community called Bidyadanga, which is Australia’s largest Aboriginal community – about two and a half hours south of Broome, with about 850 residents. I also travel to Derby, Fitzroy Crossing and Halls Creek.” Her work often involves co-ordinating with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“We treat patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety. If someone becomes unwell in a remote community with psychosis, mania or suicidal ideation, we stabilise them, give them medication, and try to get them to Broome. Some communities have tiny clinics, with only one room. We might have to keep someone safe there for days, even a week, if there are no psychiatric beds available in the state.”

“I'm always supported by an Aboriginal Liaison Officer. I work very closely alongside Aboriginal mental health workers, so often they are adept in local language. The Kimberley is a really interesting place because there are 30 different languages here and different ‘skin groups’ in the community. The Yawuru people live in Broome. So that language is not always going to apply to someone that lives in Fitzroy Crossing. They'll have their own culture and language. Understanding those different nuances is interesting, as often English is their third language.”

Greer’s work involves the kind of medicine where every skill matters, and she has also developed a deep interest in transcultural psychiatry. “You become a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. It’s very different from working in the city. There, people might see prestige in being at a major centre. But up here, you learn to do so much with so little – and get great outcomes. I just really enjoy working in a remote setting, there’s a rawness to it – and a respect for what doctors can do with limited resources.” Sometimes, reviews take place not in clinics, but on ovals, at fishing spots, or in the back of a bus.

“It’s opportunistic medicine,” she says, smiling. “You take the moment when it comes.”

“We work closely with Aboriginal mental health workers and with families. Sometimes a family will ask for a healer to come, this is known as a ‘maban man’. That’s part of their understanding of health and spirituality, and we respect that. We also incorporate bush medicine, too. If someone has a bush remedy they take at night, we include it on their medication chart like any other prescription. You always respect and integrate the culture into your treatment plan. It’s about listening. It’s about trust.”

Alongside her professional life, she and her husband Joe, a GP, are raising their, now three, children. Remote life has its challenges: long hours, few amenities, limited childcare and distance from extended family. “If I want to visit my parents in Bendigo or go to Melbourne, travel takes a long time, and it’s expensive. But the kids are having a great time. They’re learning outside, they’re part of the local surf lifesaving club and Auskick. My husband loves camping. It’s a different kind of childhood – but a good one. In the schools here they are learning some of the local Aboriginal language, called Yawuru, which is lovely.’

“It’s not always easy. But it’s a beautiful life. You work in a job that means something. And you never forget how lucky you are to be here, doing this. It was fascinating to me at the time. I think once you see these places, once you begin to understand even a little of the complexity – you're changed. You want to learn more and do more.”

The problems faced in these remote communities are numerous. Substance misuse, generational trauma, high suicide rates, lack of access to an acute mental health bed ... There's a lot of domestic violence, unfortunately, which is something that communities are working hard to combat.” However, the people she has met show resilience, and the communities support one another. “Unfortunately, the Kimberley has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. So, you're often working with families, a lot of whom have had family members who have died by suicide. So, I’m very aware of that.”

Greer is still deciding which area of psychiatry to pursue long-term, child and adolescent, forensics or transcultural mental health, but she wants to keep returning to the Kimberley. “Even when I become a consultant psychiatrist, I imagine I’ll still come back once a month for a week, to consult, to give back. I feel a real connection to this place.”

“It's very unique. Although it's hard, I still think I wouldn't change it for the world and I'm really enjoying being up here, although it can be very isolating. It does make you value everything that you have. There’s a saying up north: ‘The red pindan dirt of the Kimberley gets under your skin’. I never thought I’d be that type of person,” she says, smiling. “But I absolutely love it. And I know I’ll always come back.”

So, four years ago, the family moved to up to the Kimberley and are now based in Broome, with Greer working predominantly in the hospital and in Community Mental Health. She began in the emergency department and then in a 14-bed inpatient psychiatric unit – one of the most isolated psychiatric wards anywhere in the world. Around 70% of Greer’s patients are from Aboriginal backgrounds.

“I look after the whole of the Kimberley, basically. From the Pilbara to the Northern Territory border, right up to Kununurra and a remote community called Kalumburu in the East Kimberley. So, it's a really vast area. A very isolated and remote area. You know it's isolated when it takes four days to drive to Perth from here and 18 hours to get to Darwin.”

“I have just found it fascinating working, learning about Aboriginal culture and way of life and bush medicine, language and culture. My job takes me to Aboriginal communities; I take light planes out to remote communities. I go to the Dampier Peninsula, One Arm Point, and another Aboriginal community called Bidyadanga, which is Australia’s largest Aboriginal community – about two and a half hours south of Broome, with about 850 residents. I also travel to Derby, Fitzroy Crossing and Halls Creek.” Her work often involves co-ordinating with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“We treat patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety. If someone becomes unwell in a remote community with psychosis, mania or suicidal ideation, we stabilise them, give them medication, and try to get them to Broome. Some communities have tiny clinics, with only one room. We might have to keep someone safe there for days, even a week, if there are no psychiatric beds available in the state.”

“I'm always supported by an Aboriginal Liaison Officer. I work very closely alongside Aboriginal mental health workers, so often they are adept in local language. The Kimberley is a really interesting place because there are 30 different languages here and different ‘skin groups’ in the community. The Yawuru people live in Broome. So that language is not always going to apply to someone that lives in Fitzroy Crossing. They'll have their own culture and language. Understanding those different nuances is interesting, as often English is their third language.”

Greer’s work involves the kind of medicine where every skill matters, and she has also developed a deep interest in transcultural psychiatry. “You become a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. It’s very different from working in the city. There, people might see prestige in being at a major centre. But up here, you learn to do so much with so little – and get great outcomes. I just really enjoy working in a remote setting, there’s a rawness to it – and a respect for what doctors can do with limited resources.” Sometimes, reviews take place not in clinics, but on ovals, at fishing spots, or in the back of a bus.

“It’s opportunistic medicine,” she says, smiling. “You take the moment when it comes.”

“We work closely with Aboriginal mental health workers and with families. Sometimes a family will ask for a healer to come, this is known as a ‘maban man’. That’s part of their understanding of health and spirituality, and we respect that. We also incorporate bush medicine, too. If someone has a bush remedy they take at night, we include it on their medication chart like any other prescription. You always respect and integrate the culture into your treatment plan. It’s about listening. It’s about trust.”

Alongside her professional life, she and her husband Joe, a GP, are raising their, now three, children. Remote life has its challenges: long hours, few amenities, limited childcare and distance from extended family. “If I want to visit my parents in Bendigo or go to Melbourne, travel takes a long time, and it’s expensive. But the kids are having a great time. They’re learning outside, they’re part of the local surf lifesaving club and Auskick. My husband loves camping. It’s a different kind of childhood – but a good one. In the schools here they are learning some of the local Aboriginal language, called Yawuru, which is lovely.’

“It’s not always easy. But it’s a beautiful life. You work in a job that means something. And you never forget how lucky you are to be here, doing this. It was fascinating to me at the time. I think once you see these places, once you begin to understand even a little of the complexity – you're changed. You want to learn more and do more.”

The problems faced in these remote communities are numerous. Substance misuse, generational trauma, high suicide rates, lack of access to an acute mental health bed ... There's a lot of domestic violence, unfortunately, which is something that communities are working hard to combat.” However, the people she has met show resilience, and the communities support one another. “Unfortunately, the Kimberley has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. So, you're often working with families, a lot of whom have had family members who have died by suicide. So, I’m very aware of that.”

Greer is still deciding which area of psychiatry to pursue long-term, child and adolescent, forensics or transcultural mental health, but she wants to keep returning to the Kimberley. “Even when I become a consultant psychiatrist, I imagine I’ll still come back once a month for a week, to consult, to give back. I feel a real connection to this place.”

“It's very unique. Although it's hard, I still think I wouldn't change it for the world and I'm really enjoying being up here, although it can be very isolating. It does make you value everything that you have. There’s a saying up north: ‘The red pindan dirt of the Kimberley gets under your skin’. I never thought I’d be that type of person,” she says, smiling. “But I absolutely love it. And I know I’ll always come back.”

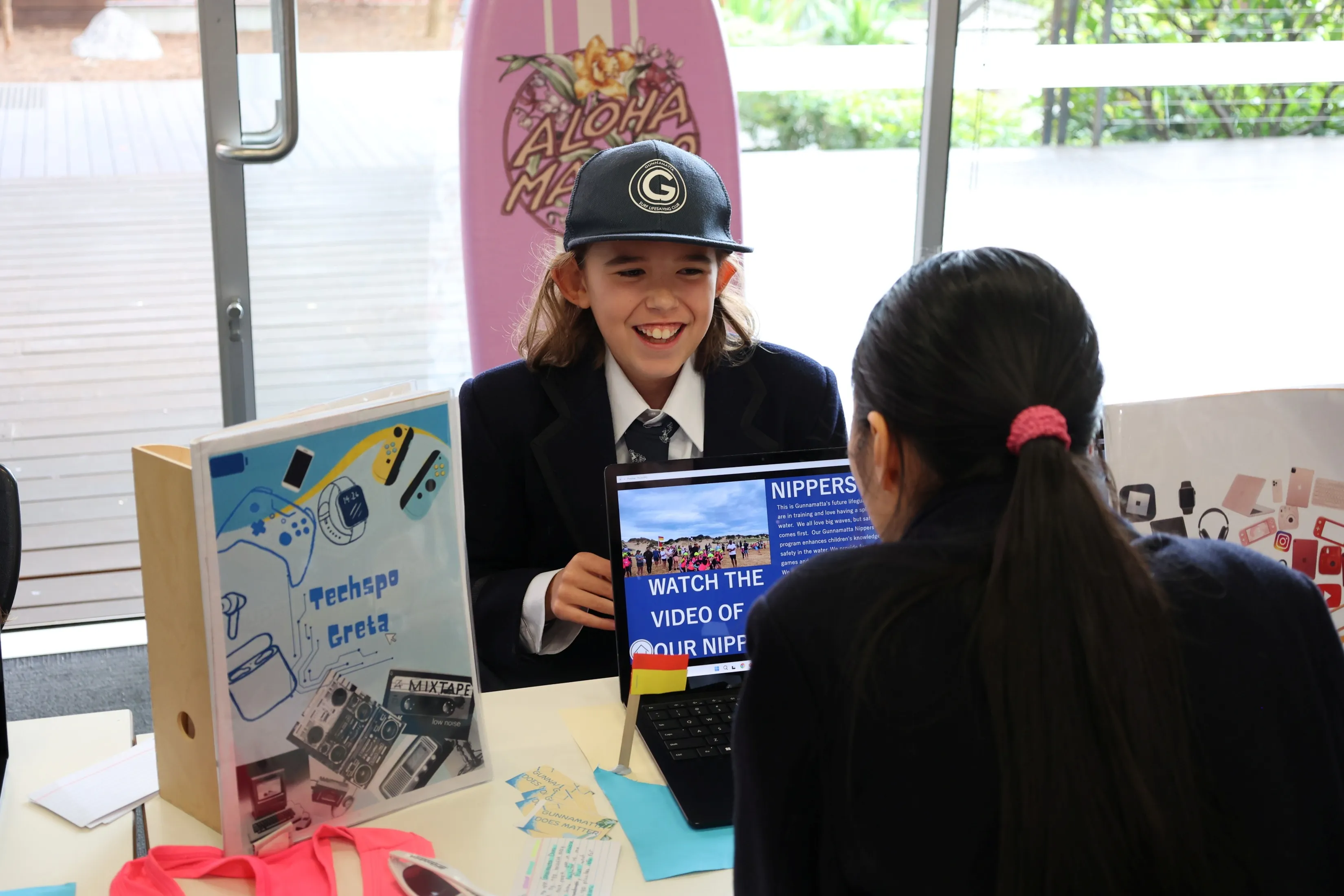

Tessa Millington (2023)

When Tessa Millington left Melbourne Girls Grammar, she didn’t expect that one of the most meaningful experiences of her life would come from a quiet courtyard in an aged care home alongside a 97-year-old woman named Dorothy, a vibrant Greek woman named Maria, and her beloved dog.

In Year 11, after watching a television program with her mother called Old People’s Home for Teenagers, Tessa was struck by the idea of intergenerational connection; where teenagers and seniors were brought together to learn from and support one another. It sparked her interest.

Searching online led Tessa to a real-world version of the show’s program, a community initiative pairing young volunteers with elderly residents in local aged care facilities. Tessa signed up, and soon after was matched with Dorothy, a non-verbal resident in a nearby home.

Tessa Millington (2023)

When Tessa Millington left Melbourne Girls Grammar, she didn’t expect that one of the most meaningful experiences of her life would come from a quiet courtyard in an aged care home alongside a 97-year-old woman named Dorothy, a vibrant Greek woman named Maria, and her beloved dog.

In Year 11, after watching a television program with her mother called Old People’s Home for Teenagers, Tessa was struck by the idea of intergenerational connection; where teenagers and seniors were brought together to learn from and support one another. It sparked her interest.

Searching online led Tessa to a real-world version of the show’s program, a community initiative pairing young volunteers with elderly residents in local aged care facilities. Tessa signed up, and soon after was matched with Dorothy, a non-verbal resident in a nearby home.

“I didn’t know what to expect ... But from the first visit, I knew it mattered.”

What followed was a year of companionship and deep emotional impact. Tessa visited Dorothy regularly after school, sometimes with her dog, who became a favourite with the residents.

“Dorothy loved him. He would just sit with her and let her pat him. Dogs are amazing in those situations.”

Dorothy couldn’t speak, so Tessa would read to her, share stories about her life, and sit with her outside in the sunny courtyard. They were often joined by Maria, a 70-year-old woman living with multiple sclerosis who loved to tell stories.

“Maria was hilarious. She and I would talk, and Dorothy would listen. It was funny and peaceful and full of meaning.” The experience was a moving one. Tessa recalls moments that were joyful and yet, heartbreaking. She and Dorothy bonded over simple pleasures, while Tessa silently witnessed the quiet decline of someone she had come to care about.

“Aged care homes can be incredibly sad places. I hadn’t seen that kind of isolation before.”

Eventually, balancing school commitments made continuing impossible and, before starting Year 12, Tessa made the difficult decision to step away from the program. “I’m glad I stopped when I did because I didn’t want to let her down. She deserved someone who could be there.” Sadly, Dorothy passed away while Tessa was studying during her final year at school. Although Tessa's time with Dorothy ended, the impact has stayed with her. “It gave me perspective. I’d never seen what neglect can look like in old age. I’m close with my grandparents, and it made me think about what would happen if they didn’t have us.”

Now in her second year in Ormond College at Melbourne University, Tessa is studying Media and Communications, with a goal of working in crisis communications – a field that combines her love for people and her interest in problem-solving.

“It’s about preparing for the worst – whether it's a scandal, a pandemic, or a political crisis – and helping organisations respond in the best way.” She is aiming for an Honours year, possibly a Masters, and sees her future in either the public or private sector. “What I love is that you’re constantly working with people, across different teams, under pressure. It feels meaningful.”

For now, Tessa's work with elderly care is on hold, but the door remains open. “I’d definitely do it again. It was one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.”

“I didn’t know what to expect ... But from the first visit, I knew it mattered.”

What followed was a year of companionship and deep emotional impact. Tessa visited Dorothy regularly after school, sometimes with her dog, who became a favourite with the residents.

“Dorothy loved him. He would just sit with her and let her pat him. Dogs are amazing in those situations.”

Dorothy couldn’t speak, so Tessa would read to her, share stories about her life, and sit with her outside in the sunny courtyard. They were often joined by Maria, a 70-year-old woman living with multiple sclerosis who loved to tell stories.

“Maria was hilarious. She and I would talk, and Dorothy would listen. It was funny and peaceful and full of meaning.” The experience was a moving one. Tessa recalls moments that were joyful and yet, heartbreaking. She and Dorothy bonded over simple pleasures, while Tessa silently witnessed the quiet decline of someone she had come to care about.

“Aged care homes can be incredibly sad places. I hadn’t seen that kind of isolation before.”

Eventually, balancing school commitments made continuing impossible and, before starting Year 12, Tessa made the difficult decision to step away from the program. “I’m glad I stopped when I did because I didn’t want to let her down. She deserved someone who could be there.” Sadly, Dorothy passed away while Tessa was studying during her final year at school. Although Tessa's time with Dorothy ended, the impact has stayed with her. “It gave me perspective. I’d never seen what neglect can look like in old age. I’m close with my grandparents, and it made me think about what would happen if they didn’t have us.”

Now in her second year in Ormond College at Melbourne University, Tessa is studying Media and Communications, with a goal of working in crisis communications – a field that combines her love for people and her interest in problem-solving.

“It’s about preparing for the worst – whether it's a scandal, a pandemic, or a political crisis – and helping organisations respond in the best way.” She is aiming for an Honours year, possibly a Masters, and sees her future in either the public or private sector. “What I love is that you’re constantly working with people, across different teams, under pressure. It feels meaningful.”

For now, Tessa's work with elderly care is on hold, but the door remains open. “I’d definitely do it again. It was one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.”

“I didn’t know what to expect ... But from the first visit, I knew it mattered.”

What followed was a year of companionship and deep emotional impact. Tessa visited Dorothy regularly after school, sometimes with her dog, who became a favourite with the residents.

“Dorothy loved him. He would just sit with her and let her pat him. Dogs are amazing in those situations.”

Dorothy couldn’t speak, so Tessa would read to her, share stories about her life, and sit with her outside in the sunny courtyard. They were often joined by Maria, a 70-year-old woman living with multiple sclerosis who loved to tell stories.

“Maria was hilarious. She and I would talk, and Dorothy would listen. It was funny and peaceful and full of meaning.” The experience was a moving one. Tessa recalls moments that were joyful and yet, heartbreaking. She and Dorothy bonded over simple pleasures, while Tessa silently witnessed the quiet decline of someone she had come to care about.

“Aged care homes can be incredibly sad places. I hadn’t seen that kind of isolation before.”

Eventually, balancing school commitments made continuing impossible and, before starting Year 12, Tessa made the difficult decision to step away from the program. “I’m glad I stopped when I did because I didn’t want to let her down. She deserved someone who could be there.” Sadly, Dorothy passed away while Tessa was studying during her final year at school. Although Tessa's time with Dorothy ended, the impact has stayed with her. “It gave me perspective. I’d never seen what neglect can look like in old age. I’m close with my grandparents, and it made me think about what would happen if they didn’t have us.”

Now in her second year in Ormond College at Melbourne University, Tessa is studying Media and Communications, with a goal of working in crisis communications – a field that combines her love for people and her interest in problem-solving.

“It’s about preparing for the worst – whether it's a scandal, a pandemic, or a political crisis – and helping organisations respond in the best way.” She is aiming for an Honours year, possibly a Masters, and sees her future in either the public or private sector. “What I love is that you’re constantly working with people, across different teams, under pressure. It feels meaningful.”

For now, Tessa's work with elderly care is on hold, but the door remains open. “I’d definitely do it again. It was one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.”

Thank you to Old Grammarians Greer and Tessa for taking the time to speak with us and for sharing their stories so generously.

Thank you to Old Grammarians Greer and Tessa for taking the time to speak with us and for sharing their stories so generously.

Thank you to Old Grammarians Greer and Tessa for taking the time to speak with us and for sharing their stories so generously.

%20resized%20landscape.webp)

.webp)

.webp)